Suicide of the Left

What the hell happened to American leftism in the 1970's?

K.J.L. Kjeldsen

Table of Contents

III. Peter Turchin: Structural-Demographic Analysis

V. A Rough Sketch of the Continuing Trends

Introduction

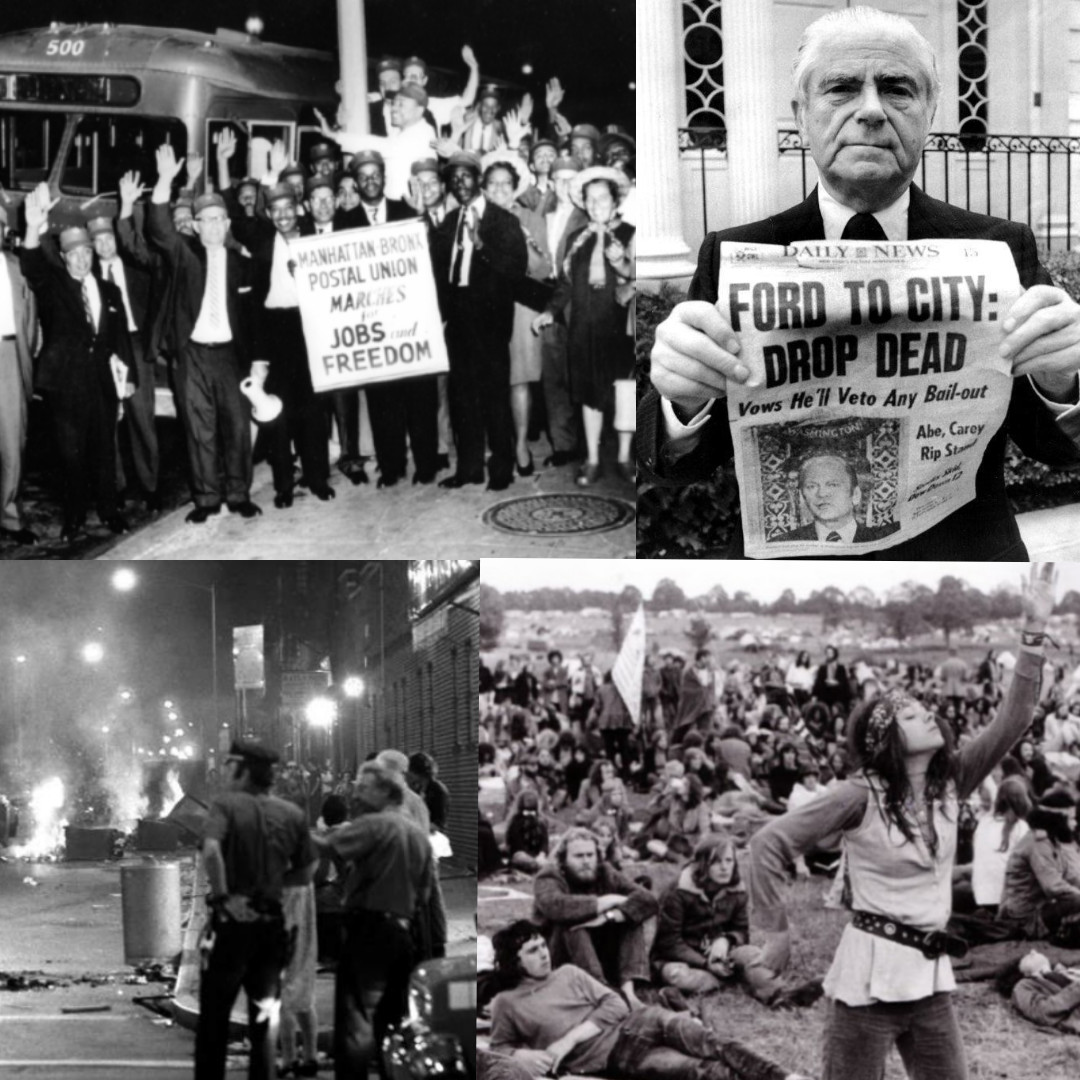

In 1970's America, the Democratic party abandoned the working class. The strategists and thought-leaders of the party started to drift from the economic left, and began to seek a new voter base: the white-collar professional class. This educated, liberal elite, which was one part of the Democratic coalition, decided to exclude the interests of labor, and run the coalition themselves. They then embarked on a course of legislation and party reform with the aim of openly privileging the interests of the professional-managerial class. This trend took hold, and only became more pronounced in the decades that followed. Accompanying this shift in politics was a decline in the power of labor unions, falling real wages for workers, and a cultural attitude of individualism that scorned collective movements.

This would be a monumental shift in United States politics, since it meant that the alignment of the interests of labor with the Democratic party, which began only forty years before, under FDR, would start to break down. The result was that American workers, especially the blue-collar workers, those without college degrees, and the shrinking number of skilled and organized laborers, began to feel unmoored from a broader political project or identity. There were dire consequences. Over time, as the working class felt further and further alienated from the Democratic party, they became increasingly open to appeals from the right. Meanwhile, the monied interests in the system had no organized base of laborers to oppose their political interests. The greatest excesses of capitalism were permitted, while union membership has dropped to multi-decade lows.

We have observed the accelerating power of capital in the past number of decades – the staffing of Obama’s administration with a list sent in an email by Citigroup, the repeal of Glass-Steagall under Bill Clinton, the deindustrialization of middle America that the Democrats ignored (and that Hillary Clinton openly mocked the victims of, during the 2016 election), the rise of drug addiction and welfare dependency, the 2008 crash and the passing of the debt onto the public ledger. All of these events, scattered throughout the past half century, and with their own proximate causes, nevertheless have their origin in the shift of the 1970’s.

The fact that this shift even happened at all is rarely discussed in mainstream political discourse in America; indeed, many well-meaning liberals still conceive of themselves as the defenders of the working class. But we must not only understand what happened in the 1970’s, but how it happened, and – most importantly – why. The 1970’s was not the decade I would have thought to examine for an explanation of the strange unrest, the polarization, and the sense of helplessness that we experience today. But I repeatedly came upon sources which located the 1970’s as the decisive point. I eventually came to recognize that this was the decade when the American left committed suicide.

The three most important thinkers who elucidated this historical realignment – and in whose works all of the major points of the story are outlined – are an American political activist in the tradition of Kansan populists, a British documentary filmmaker known for his eerie, dreamlike style, and a Russian academic with an innovative theory of history.

I. Thomas Frank: Politics

Thomas Frank was born in Kansas, and was a college republican. But as he grew older, and Frank’s views shifted to become more left-wing, he became baffled at the contrast between the political history of Kansas and the current political reality. In his book, What’s the Matter with Kansas? – its title taken from an 1896 editorial, excoriating the state’s populist political leaders for driving capital out of the state – Frank laments that the populist movements which originated in Kansas in the late 19th century were now totally extinct. The denizens of the state now voted for pro-business, pro-free-market, anti-regulation, anti-welfare politicians on the American right wing. But rather than seeing these politicians as acting contrary to their interests, the people continued to elect them, because they sided with the rural, Christian, conservative populace on a slew of social issues. These social issues increasingly served as a wedge between Democrat and Republican, as the citizenry focused to a heightened degree on the culture war. Economic issues took the side stage.

Frank has spent his career trying to construct a coherent case as to why this is. While What’s the Matter with Kansas? caused quite a stir – and managed to offend both the liberals and the conservatives – Frank’s most instructive work on the abandonment of economic issues by the left is Listen, Liberal. In the book, Frank gives a description of the new, professional-managerial class that is identified with modern liberalism. Importantly, he tells the story of how the liberal elite captured the party from the working class. The pivotal moment was the 1970’s.

In 1968, the Democratic candidate for president, Hubert Humphrey, lost by a large margin in the electoral college to Richard Nixon. The Democratic party had been primarily supported by organized labor up to that point, ever since the public works projects and worker protections instituted by FDR. But Nixon’s winning coalition was “the Silent Majority” out in the suburbs: the middle-class, white, “average American”, who had fled the crowded cities. The loss prompted soul-searching among the Democrats, which led to the creation of The McGovern Commission.

The result of the commission’s reforms was that, between 1968 and 1972, the interests of labor were relegated to a lesser status in terms of importance to the party. After all, the labor unions, as a voting base, couldn’t beat the Silent Majority (Frank points out that the unions did the most legwork of anyone during the campaign, but ultimately, this didn’t matter). The Democratic party therefore began to realign itself in terms of the new voter base it meant to represent. They considered the blue-collar workers and the unions to be obsolete, and became enamored with an imagined future in which most or all of the country joined the ranks of the white-collar sector. To secure their future electoral solvency, the Democrats decided to become a white-collar party.

In 1971, a manifesto of sorts circulated among the Democratic intelligentsia. It was a book called Changing Sources of Power, by Fredrick Dutton – a lobbyist, and Democratic strategist. His book provided the ideological basis of the McGovern reforms. Dutton argued that the defense of the working person was now largely irrelevant, because the future was a society guided not by mass politicians, but by “aristocrats – en masse”. He was speaking of a growing upper-middle class generation of college-educated liberals, who would “recover the human condition from technological domination” and “refurbish and reinvigorate individuality.” Dutton wrote, of this new class of liberal ubermenschen, “They define the good life not in terms of material thresholds of ‘index economics’, as the New Deal [and] Great Society… have done, but as the fulfilled life in a more intangible and personal sense.”

A journalist, Theodore White, recorded the reaction of the labor leaders as they realized that the McGovern Commission, while it included measures to protect marginalized demographics, such as women, and minorities, also included reforms that effectively pushed labor interests to the side. Al Barkan was director of the AFL/CIO’s political arm in 1972 –which was named, with multiple levels of irony, COPE (the Committee On Public Education). White quotes him as saying that labor “was being taken for granted”, and “We aren’t going to let these Harvard-Berkeley Camelots take over our party.” Unfortunately, Barkan was indeed “coping” with the inevitability of the professional takeover.

White wrote, “The new reforms had by 1972 given categorical representation to young people, to women, to blacks – but yielded no recognition at all, as a category, to men who work for a living.” Did the new, yuppie-centric coalition still want to work for a living? Political scientist Byron Shafer, who has studied the 1972 reforms, writes that, “After reform, there were two parties each responsive to quite different white-collar coalitions, while the old blue-collar majority within the Democratic party was forced to try to squeeze back into the party once identified predominantly with its needs.”

Thomas Frank located these reforms as laying the foundations for the culture war. The Democrats had made their core identity the defense of identity groups. Meanwhile, Frank writes: “Neglecting workers was the opening that allowed Republicans to reach out to blue-collar voters with their arsenal of culture-war fantasies. No serious left politician would make a blunder like that on purpose.” They did this because they did not really believe in left politics in any meaningful sense any longer. As Dutton had argued in his 1971 manifesto, the political theories centering around contending economic classes were outdated. The future was the Now Generation, whom he called, “an affluent and liberating upper-middle-class element.”

Rather than the elite dominating the poor and the working class, stepping on them from above, the new Democratic generation held the promise of an elite that would uplift the downtrodden. The Democratic plan, effectively, was to endlessly expand the elite. The working class was destined to die out – and the Democratic elite were happy to give them a final push. The dream was that the worthy among the working class could be pulled up, into the aristocracy.

Dutton called the blue-collar workers, “the principal group arrayed against the forces of change.” As Frank points out, this was not entirely untrue: there have always been reactionary elements of the working class. In fact, one could even say that it is the rule for the working class and not the exception. In those days, George Wallace had just mounted a pro-segregationist presidential run, supported by working-class whites. The blue-collar workers in popular culture were portrayed as aging bigots (such as in All in the Family), and thus the former constituents of FDR were no longer enshrined into the leftist consciousness as heroic. That the working class was no longer relevant was a good thing – or so the current leftist wisdom went. Dutton wrote, “In the 1930’s, the blue-collar group was in the forefront. Now it is the white-collar sector… the college-educated group.”

Obvious, the McGovern Commission did not work out as planned. Ultimately, the Democrats chose George McGovern himself as presidential nominee. This decision was a massive failure, as was the Democrats’ attempt at a new white-collar voting base. Frank explains:

“McGovern had a decent record on working-class issues, but the public identified him with the Democratic Party’s new favorite group: affluent suburban liberals. In fact, according to one account, McGovern did better among these ‘highly skilled professionals’ than he did with the Democrats’ traditional blue-collar constituency, many of whom were lured away by the Richard Nixon reelection campaign. What this meant was that McGovern romped in prestigious college towns and also came out ahead in the college-heavy and distinctly professional state of Massachusetts. Nearly everywhere else, however, his particular demographic appeal was a recipe for disaster. He went down in one of the greatest electoral wipeouts in American history.”

The Vietnam war, which had driven social unrest in the country for more than decade had increased the cultural polarization and the intergenerational tension. The anti-war protests were sustained, often erupted into violence, and provoked violent police responses; meanwhile, some of the blue-collar workers had rioted in favor of the war. Then, the Watergate scandal rocked Washington, and shocked the public. Nixon eventually pulled out of Vietnam, and ended the conflict. Watergate, meanwhile, would end his presidency in shame.

The reaction to Watergate saw a huge number of new Democrats elected to Congress in the year 1974. They were made in the image of Dutton’s ascendant, liberal aristocracy. They did not speak in the language of populism, of labor interests, or of economic leftism. The star among them was the new senator, Gary Hart. His campaign speech was named, “The End of the New Deal” – making crystal clear Hart’s position on economic leftism. The historian Jefferson Cowie wrote, of the incoming Democratic lawmakers of this period: “The new Democrats came out of the anti-war protests and the McGovern campaign, the Peace Corps and the women’s movement, the professions and the suburbs, but not the union halls and the wards.”

Modern-day liberals tend to place the blame for America’s rise in extreme individualism in the 1980’s with Ronald Reagan. But Thomas Frank, having charted these trends in the Democratic party, elucidates how the break with the New Deal tradition, and the Democratic abandonment of collective politics paved the way for extreme individualism four years earlier. That was the first time when the Democratic elite’s calculated realignment started to bear fruit. In 1976, Jimmy Carter was elected.

Jimmy Carter reoriented the liberal political conscience from the material and economic and into the personal, and the moral. The Democrats had already worked to establish themselves as primarily concerned with a set of identity and social issues. Carter put solar panels on the roof of the White House, in order to set a good example, but cancelled public works projects. He emphasized personal responsibility, and the duty to be decent to one another, while he and a Democratic Congress ceded more and more to the large financial institutions. Frank writes:

“With the help of a Democratic Congress, [Carter] enacted the first of the era’s really big tax cuts for the rich, and also the first of the really big deregulations. As though to prove how tough and post-partisan he could be, in 1980 he and Paul Volcker, his hand-picked Fed chairman, put the country on an austerity diet that was spectacularly punishing to the ordinary working people who had once made up the Democratic base.”

Perhaps most telling was a 1981 interview with Carter adviser Alfred Kahn. When asked about the political arguments over deregulation and inflation, Kahn, an economist, had this to say: “I’d love the Teamsters to be worse off. I’d love the automobile workers to be worse off. You say that’s inhumane; I’m putting it rather badly but I want to eliminate a situation in which certain protected workers in industries insulated from competition can increase their wages much more rapidly than the average without regard to their merit or to what a free market would do, and in so doing exploit other workers.”

Kahn’s argument is particularly hostile to the leftist defense of the worker’s interests. Collective bargaining, which represented one of the last means of workers banding together to protect their mutual interests, in a sense that would ensure their survival and the continuation of their quality of life – is here slandered as unfair, because only the free market should be able to choose what should be paid to which worker, on a strictly individualistic and meritocratic basis. The new Democrats were not simply disinterested in preserving the collective bargaining power of unions – in fact, they had become vehemently opposed to it. Frank writes about how, throughout the 1980’s, the Democrats continually spoke in the language of the “death” or “end” of the New Deal. A political scientist in 1985 wrote: “The collapse and end of the New Deal is one of the most frequently reported events in American media.”

As such, Carter’s defeat itself was even taken as evidence that the New Deal had died – yet again. The day after Carter lost the election, Senator Paul Tsongas was quoted as saying, “Basically, the New Deal died yesterday.” This was in spite of the fact that Carter himself was borne on the ascendancy of Democrats who were themselves hostile to the New Deal. In reality, the economic suffering of Americans, which had gotten out of control with the problem of stagflation, as well as Carter’s foreign policy blunders, were to blame.

But these factors were ignored. In the future, every time the Democrats lost during this era, they repudiated the New Deal, and took the loss as evidence that they had to move away from economic issues. When they won, however, they still repudiated the New Deal, and took the success as evidence that they had to move away from economic issues. The historian William Leuctenberg wrote: “It was far from clear why if, as Gary Hart claimed, the New Deal was dead in 1974, it was necessary for him to kill it off in 1980 and again in 1984.”

These new Democrats came to be known, in ideological terms, as “neoliberals”. Their ideology was solidified in “A Neoliberal’s Manifesto,” by Charles Peters, written in 1983. The tract blamed the unions for all of the country’s industrial problems, criticized Social Security as wasteful and ineffective government welfare, and attacked public school teachers. “Our hero,” Peters wrote, “is the risk-taking entrepreneur who creates new jobs and better products.”

It should scarcely require mentioning, but this passage reads like it could have been penned by Von Mises or Rothbard, rather than a Democratic strategist or leftist thought-leader. What it reveals is that the new Democrats, by virtue of the fact that they came from a strictly professional-managerial background, and were not particularly representative of the working people, were inherently conservative in many respects. While they tried to graft the leftist dream of egalitarianism onto aristocracy – with the vision of a rising liberal elite that could expand to encompass everyone who worked hard enough, and learned enough skills – ultimately, they were hostile to the working class as people.

Thus, we may say definitively that the completion of this realignment involved a new set of political assumptions upon which the Democratic party operated. In the 1970’s, the Democrats began to sees themselves as civilized, and the workers as unwashed, barbaric heathens who needed to be changed, or saved from themselves. They affirmed the institutions and the meritocracy that placed them into the positions of power. This was reflected in both their stated ideology, and their enacted policy. The party that supposedly stood for labor didn’t believe in the politics of labor any longer.

II. Adam Curtis: Culture

Adam Curtis is known for artistic, roving documentaries that span nations and decades. His usual haunt is the BBC, and many of his fans probably associate him with the eerie choices of soundtrack, sampled from the likes of Aphex Twin and Nine Inch Nails, set to archival footage of strange, obscure, or forgotten moments. He often meditates on the increasingly fake world in which most people now live, on the corrosive effects of capitalism and consumerism on culture, and of the foreign policy blunders of western nations.

A common theme in Curtis’ filmmaking is a radical re-evaluation of the 1960’s radicalism on American society. Curtis calls this phenomenon, “the counter-culture”. It consisted of hippies, artists, writers, musicians, activists, vagabonds, advocates of hallucinogenics, back-to-the-landers, and so on. The typical narrative surrounding the counter-culture is that they were a radical force for change that arose around the time of the Civil Rights Movement, and often, the counter-culture is held up as a contributing factor in the success of the Civil Rights Movement. The radicalism of the 1960’s is therefore given credit for the positive societal changes that were to follow.

Curtis, on the other hand, holds that the 1960’s radicals were an entirely impotent, conservative force. Far from having contributed to the success of the Civil Rights Movement, they were the representatives of an entirely different kind of ideology – that of individualism. Rather than a threat to the system, the radicals diffused any potentially dangerous energy through the harmless medium of individual self-expression. This made the counter-cultural, far from a subversive development in American culture, in fact as American as apple pie.

While the expansion of democratic rights and civil liberties to more people than ever had awakened the collective power of mass democracy, it also expanded the appeal of individualism. Rather than a vision of radicalism as a community, or a whole society coming together for their mutual interests, and challenging the old power of tradition, dogma, and the state, individualistic radicalism simply sought to deliver the individual from all broader obligations, duties, or limitations. This meant that the individual was not liberated so he could simply become part of some new collective movement: liberation was to be found in individualistic expression.

In his 2021 docuseries, Can’t Get You Out of My Head, Curtis details how Kerry Thornley and his friend Greg Hill founded the pseudo-religion of Discordianism during this era. Discordianism, while nominally based on the worship of the goddess Eris, ultimately only holds a symbolic respect for the Greek goddess as a representation of ungovernable, purely individualistic chaos. The philosophy of Discordianism rejects the authority of all externally-imposed political or moral ideas, and urges the individual to create and define their own reality. Thornley was heavily influenced by the novels and ideas of Ayn Rand, whose philosophy of Objectivism represented an extremist form of individualism.

Meanwhile, major counter-cultural figures, like Timothy Leary, advocated for people to gain a personal experience of enlightenment through the use of drugs like LSD. “Don’t politick, don’t vote,” Leary urges, in archival footage from 1967 that Curtis dredged up for his 2016 film, HyperNormalisation. “There are old mens’ games… impotent and senile old men who want to put you onto their old chess games of war and power.” The dream of the advocates of hallucinogenic drugs was that the psychedelic experiences brought on by the drugs would transform the hearts and minds of those who used them. Leary prophecized an “LSD society” that would have less interest in things like warfare. Thus, rather than having to do the difficult legwork of organizing – both in terms of political activism, and organizing labor for the purposes of collective bargaining – one could simply preach the individual enlightenment of acid, and wait for society to change of its own free will. The games of war and power did not interest in the hippies: they wanted an easy way out.

This isn’t to say that there was no effective radicalism in the 1960’s: after all, the successes of the Civil Rights Movement itself should testify to this, as the movements that coalesced around these issues, included forms of radicalism, such as the Black Power movement. But Dr. King and his contemporaries marched with labor unions, and utilized strikes in order to achieve their ends.

The Civil Rights Movement was not a strictly individualistic movement that tried to change hearts and minds: it involved organizing to challenge political power. There was widespread civil unrest in response to the horrors of the Vietnam War, and the ugly racial oppression in America. This very fact means that some of the 1960’s radicals were still able to, in Curtis’ turn of phrase, “give themselves up” to a collective project. To the extent that they were still able to do this, they were successful. As Curtis points out, the radicals were more persistent in opposing Vietnam than the radicals of the 2000’s would be in opposing the war in Iraq. What changed, in Curtis’ view, was that the radical individualism of the counter-culture took hold and mostly extinguished the faith in collective action.

Curtis finds the Black Panthers and the Black Power movement to be particularly laudable, if for no other reason than that their adherents took a realistic view of power relations, and understood that it was only through organizing and agitating that they could challenge the system. Stokely Carmichael, for example, was one of the founders of the idea of black power. He gave a fiery speech rousing the audience to radicalism, when the more moderate Dr. King didn’t arrive to speak in time. Carmichael seized the opportunity. “It wasn't a question of morality...” Carmichael explains. “We black people had no power, and we had to have some power... The only kind of power we could have was: black power.” While revolutionary thinkers such as Bobby Seale gave speeches in Harlem, west coast Panthers had running shoot-outs with the police. There was a serious undercurrent of fear among white society created by the black radicals. As the popular wisdom goes, the fear of the more radical elements may have aided the more stubborn elements of white society in acquiescing to the reasonable civil rights demands of moderates like Dr. King.

In spite of these successes, few of the revolutionary movements of 1960’s America managed to sustain themselves. Intelligence agencies and police departments inundated revolutionary organizations with undercover officers. Some of the Black Panthers found themselves facing charges of terrorism in public trials. While some Black Panthers successfully defended themselves in court, the revelations about the large number undercover operatives radiated suspicion through the entire counter-culture. During the trial of Afeni Shakur, for instance, when her cell of Black Panthers were charged with planning to plant bombs throughout the city, the undercover officers admitted on the stand that they had organized everything, purchased the bombs from another undercover officer, and used government funds to do so. According to the undercover officer, they’d had to plan everything because most of the black radicals actually had dwindling interest in the legwork of organizing, and were off doing “their own shit”. Afeni Shakur was acquitted, but the revelations of the trial demonstrated the disintegrating trust within revolutionary movements, and the paranoia of the intelligence agencies – who, in the course of trying to catch those planning attacks on America, had planned, organized and prepared an attack on America.

The trend of collective power starting to disintegrate also applied to the unions. An early example of this failure of collective action is detailed in the work of Harry Caudill, in his 1963 book, Night Comes to the Cumberlands. The Cumberlands were part of the vast mining region in Appalachia, and Caudill raised the alarm in the year 1963 that automation had displaced thousands of workers, and the mining companies had largely withdrawn their paternalism which had previously supported entire communities of miners and their families (this was because the mining companies owned all the stores, the hospitals, the lodging, and so on). The displaced workers were unable to support themselves and largely turned to welfare to survive. Many of them were now chronically sick or disabled from their days working the mines. While the collective action and outright rebellions of the workers during the late 1800’s – and again in the oughts, the ‘violent teens’ and the twenties – had represented a real power to challenge the wealthy mining magnates, now the workers were unable to agitate to an effective degree.

In response to this social dissolution, the previously loud and zealous radicals of the 1960’s – both black and white – largely faded into the background. This shift in the radical’s consciousness, occurred sometimes between the 1960’s and the 1970’s. The poster-child for this new radicalism was the singer, Patti Smith, whom Curtis follows around a tour of 1975 New York City in HyperNormalisation. Patti Smith recounts watching impoverished and indigent people standing in front of the movie theater, watching the free clips that play on repeat, simply because they have nothing else to do. She points out her favorite graffiti, laughing and smiling as she reads, “Jose and Maria forever” from the spraypainted concrete. She represents, according to Curtis, a new type of individual radical, who did not politically agitate against the decaying status quo, or fight the powers-that-be. Rather, one simply “watched the decaying society with a cool detachment.”

|

| Timothy Leary: "Don't politick, don't vote." |

In the words of Curtis: “Radicals across America turned to art and music as a means of expressing their criticism of society. They believed that instead of trying to change the world outside, the new radicalism should try to change what was inside people’s heads. And the way to do this was through self-expression, not collective action. But some of the left saw that something else was really going on: that by detaching themselves, and retreating into an ironic coolness, a whole generation were beginning to lose touch with the reality of power. One of them wrote at that time, ‘It was the mood of the era, and the revolution was deferred indefinitely. But while we were dozing, the money crept in.’”

Patti Smith herself wrote, of her own detachment from politics: “I could not identify with the political movements any longer. All the manic activity in the streets… in trying to join them, I felt overwhelmed by simply another kind of bureaucracy.” Like other radicals of the time – who dreamt not ten years before of changing the world through revolution – she was now living in the abandoned buildings in Manhattan. Meanwhile, throughout the city, greedy landlords hired gangs to burn down whole buildings to collect the insurance, as soon as they no longer were profitable.

By 1975, the city’s finances more or less collapsed, and the bankers were allowed to take control of the budget through a committee in which they held eight out of nine seats: the Financial Control Board. President Ford told the city that the Federal government would not come to their aid, and that he would veto any bail-out. The Financial Control Board immediately imposed austerity on New York, and union workers employed by the city – including teachers, police, and firemen – were laid off. Curtis documents in HyperNormalisation how the unions raged against the injustice of a worker who made eight or nine thousand dollars a year being fired to balance the city’s budget, when the bankers who now controlled the city’s finances could make sixty million on a single transaction. But in spite of all the popular outrage, nothing was done to oppose the austerity measures. The individualist radicals didn’t have any means of doing so, and couldn’t imagine anything that could challenge power from within their ideology. Meanwhile, the unions had declined in power. They no longer had a serious voice within the Democratic party, which was reinventing itself as a party for upper-class technocrats and individualist entrepreneurs.

Expressed in the most general and abstract possible terms, Adam Curtis’ overall critique of modern society is that it has created what he calls a “dreamworld” in which the inhabitants live. This dreamworld is more real to them than the material world governed by the laws of physics, of nature, and of power relationships. As to the character of this dreamworld, it is the cultural narrative. As to how it is created, it is given form by the elite class of society, by the politicians, the media, and perhaps most importantly, by the artists, musicians and entertainers.

People escape into this dreamworld when the world becomes too complicated to comprehend, and the individual consequently begins to feel frightened and alone. The safety and simplicity of the dreamworld allures. “Even those who thought they were attacking the system,” Curtis says, “the radicals, the artists, the musicians and our whole counter-culture, actually became part of the trickery, because they too had retreated into the make-believe world – which is why their opposition has no effect, and nothing ever changes.”

The radicals and activists having succumbed to a feeling of detachment, the laborers and the unions began to feel betrayed. Everyone felt the disconnectedness and stagnation in the system. This resulted in a zeitgeist borne on the feeling of anxiety and suspicion throughout the Nixon era. This angst emanated from the top of the society – Nixon himself. During the Oval Office recordings of his presidency, Nixon repeats to himself, “the professors are the enemy, the establishment is the enemy, write that on the blackboard, one hundred times… the establishment is the enemy, the establishment is the enemy…” Curtis attributes Nixon’s paranoia to his intuitive knowledge of his own precarity, and the growing power of finance that was threatening to undermine democracy. Accordingly, he conspired with former intelligence operatives to spy on his political opponents. Nixon, genuinely fearful that a corrupt establishment was undermining him at every turn, ended up seeding corruption in his own administration in his effort to fight against it. This corruption, once exposed, only accelerated the feeling of anxiety throughout the entire culture, because the people now felt increasingly that they couldn’t trust the authorities.

This increasing collapse of social trust manifested itself in the form of widespread addiction to valium. The drug was prescribed initially to women, but more and more men began to take the drug as the factories churned out millions of pills a weak. Americans from the suburbs, who increasingly reported to their doctors and therapists that they felt alone, anxious, and listless, were prescribed the drug, which made them feel safe and protected. This was yet another social trend that was represented even at the top of American society – when Betty Ford, the wife of Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, came out to the American public and admitted her own addiction to valium. The flight from an increasingly troubled society into drug addiction represents a literal escape that parallels the artistic escapism of individualism – not to mention that escapism through drug use was also part of the hippie movement.

Curtis’ explanation of this shift in the attitude of radicalism – from a worldview steeped in the realities of power and mutual class interest, to an ideology of hyper-individualism and self-expression – offers some explanation as to how the abandonment of labor was able to take place within the Democratic party. Because of the weakness of mass democracy, the coalitions that carried presidential candidates into office became ever more fragile. Increasingly, people were not able to cooperate effectively, and became less like a voting block and more like a cluster of confused, self-centered individuals. This accelerated the collapse of public trust, which in turn fueled suspicion, and created a vicious cycle. By the time of the 1980’s, the reigning ideology became even more self-centered, hedonistic, and unapologetic, and the faith in collective movements had vanished.

III. Peter Turchin: Structural-Demographic

Analysis

Peter Turchin began his career studying population ecology. At the time, Turchin received widespread pushback when embarked on the quest of creating mathematical models to explain population dynamics across species. Once Turchin felt he’d accomplished this with animal populations, he began to study humans. Even though modern human beings are affected by far more variables, such as the unpredictability of human choices, modern technology, and global economic forces, Turchin simply took this as a challenge. The result was the field of cliodynamics – the analysis of historical societies and the mathematical modeling of the laws governing human history.

Turchin applied his theories to the United States and its history. His book on the subject, called Ages of Discord is subtitled, “A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History”. Turchin analyzed all the available data going back centuries, on factors such as real wages, rates of immigration, average age when people first got married, average height, average life expectancy, and so on. By assembling this host of factors into a series of equations, Turchin charted the data, and showed the correlation between these factors: when real wages are up, average height will likely be higher, and life expectancy longer. The result is an index of popular well-being. The well-being or immiseration of the United States, at any given period, can be shown on a graph.

What one may immediately notice are the crests and troughs of the well-being index (the rate of immigration, which is a negative well-being indicator, is inverted on the graph). Turchin demonstrated that these highs and lows do not happen at random. In fact, they’re the components of what is called a secular cycle. Turchin writes, “A typical historical state goes through a sequence of relatively stable political regimes separated by unstable periods characterized by recurrent waves of internal war. The characteristic length of both stable (or integrative) and unstable (or disintegrative) phases is a century or longer, and the overall period of the cycle is about two to three centuries.”

The driving forces behind this oscillation between integrative and disintegrative periods of society are oversupply of labor, and the subsequent oversupply of elites. Labor supply is the determining factor of popular prosperity – when there is an oversupply of labor, wages fall, and more workers slip into poverty. Falling real wages mean more revenue for the elites, and the oversupply of labor therefore always triggers more wealth to flow upward into the elite class. The elite class tends to expand during times of inequality as well. Eventually, the number of elite aspirants exceeds the amount of elite positions available. This leads to societal instability. Turchin writes, “Increased intraelite competition leads to the formation of rival patronage networks vying for state rewards. As a result, elites become riven by increasing rivalry and factionalism.” The consensus among the authorities breaks down, and in-fighting begins. Oftentimes, this progression of events has led to increased partisanship, social unrest, rioting, and overall uptick in violence, and even civil war. “As all of these trends intensity, the end result is state bankruptcy and consequent loss of military control; elite movements of regional and national rebellion; and a combination of elite-mobilized and popular uprisings that expose the breakdown of central authority.”

This pattern has been repeated throughout history, and modeled on many historical societies. What does Turchin’s model elucidate about the United States? Judging by the graph shown earlier, there are clearly some correlative factors that seem to show the waxing and waning of social harmony in America. If we examine the graph, it is clear that the integrative trends in the United States began to reverse around the 1960s, and began moving fully in the opposite direction by the end of the 1970’s. This is what is called a trend reversal, and it indicates that the first part of the current secular cycle, in which the social trends of the United States were all moving in a positive direction, ended during that time. The 1970’s began our disintegrative phase, and Turchin predicts that we will not hit the nadir for three or four decades. This would mean that, for structural-demographic reasons, the 1970’s were the fated era when America’s workers would see their power decline, and the elites would see their ranks and fortunes expand. The overproduction of elites that followed is, according to Turchin, the cause of our current climate of political polarization and social tension.

From 1929 (just before the period of New Deal politics) to the 1970s (the end of which marked the trend reversal), the top fortunes in American declined “not only in relative terms (in comparison with median wealth), but also in absolute terms (when inflation is taken into account),” Turchin writes. “The numbers of top wealth holders also declined. If in 1900 there were 19.3 millionaires per one million of general population, in 1925 this number shrank to 13.9, and between 1925 and 1950 it plunged to 5.8… Most of this drop took place during the Great Depression.” This decline in fortunes applied equally to the business world as it did to private fortunes. Between 1929 and 1933, of the eight thousand banks which were members of the Federal Reserve System (which were the largest banks in the country), over three thousand failed. About half of the 16,000 smaller banks failed.

Meanwhile, the common workers received more aid from the state than they’d ever had access to, and the unions were empowered beyond anything they’d experienced before. Federal spending, expressed as a fraction of GNP, was doubled during the 1930’s, and this development remained permanent in the subsequent decades. With the state investing into the bottom of society, and with more demand for labor than there were workers, laborers in America – particularly skilled laborers – saw their standard of living increase. As a result, the elites languished and the commoners prospered. But these trends, agreeable as they may seem to anyone of a left-wing bent, contained the seeds of their own undoing.

The prosperity led to upward mobility, which creates elite overproduction. The demand for higher education is one metric for measuring the rate at which people are being admitted into the ranks of the elite. One way to gauge this demand is by what people are willing to pay for entry. The secular cycles are clear when we look at the cost of Yale Tuition relative to the salary of a blue-collar worker.

Turchin writes, in explanation of the data: “The cost of attending Yale responded to short-term fluctuations in demand resulting from young males being drafted. This effect happened in all major conflicts except the Vietnam War, which did not produce a downtick because of exemptions and deferments available to college students… The second… cycle began with a period of low demand from the 1930s until 1980, followed by a rapid increase and high demand to this day. It is startling to note that, according to this index, Yale education is less affordable today than it was during the Gilded Age.” (The bit about the college students, the future leaders of society, getting to avoid the Vietnam war, which happened during the 1960’s and early 1970’s, is perhaps one of the most significant expressions of the coming trends than anything else).

This is only one example of a data point revealing the expansion of the elite ranks, but the trend overall is clear. The share of wealth owned by the top one percent richest Americans (and their incomes) bottomed out by the 1970’s. This allowed inter-class mobility, as it was a vacuum that prosperous middle and upper-middle class people could rush to fill. As they did, the entry to the elite got more expensive.

Meanwhile, the supply for labor, which had always fallen short of the available, gainful employment, began to rise closer and closer to equilibrium with the demand. Sometime in the early-mid 1970’s, the supply began outstripping the demand. The reasons for this were manifold. One was immigration. In 1965, a reversal of immigration policy allowed for more the arrival of more foreign workers. Turchin: “However, the initial rise during the late sixties and seventies was primarily driven by… internal demographic growth. The generation that reach marriageable age during the Great Depression and World War II had fewer babies than the post-war generation (the parents of baby-boomers). When baby boomers began entering the job market in massive numbers after 1965, they quickly drove the supply curve up above the demand.”

This shifted the balance of economic power away from the hands of the workers. The elites then behaved as they always do, and began to maximize their profits. Businesses began to flout union regulations, and offer decreased wages (especially for non-union workers). Turchin: “The frequency of union election campaign in which employers used illegal firings as a disruptive and intimidating tactic grew during the 1970’s and reached a peak in the early 1980’s, when roughly one in three unionization campaigns was marred by illegal firings.” Union membership began to decline.

In fact, when we look at almost every single indicator available, we find that all of the factors driving the popular well-being began to reverse themselves. Meanwhile, all of the trends of elite incomes and wealth inequality also reversed, and the elites began to plunder society once again.

Perhaps most important to understanding why the elites behaved as they did is in understanding the social consequences of the Structural-Demographic Theory. We tend to think of the adoption of ideologies as the result of freely-made, intellectually-considered choices; but in fact, we can actually predict the prevalence of radical ideologies based on the popular well-being, and amount of internal conflict in a given society. As a society becomes impoverished and poorly-run, and when large numbers of young men can’t find work, radical ideas find fertile soil to grow. As older generations of moderates retire, and political violence begins to explode, the amount of radicalism in a society explodes. This coincides with a period of sociopolitical instability.

This instability will reach a peak, and then begin to decline, as all of these social cycles are subject to trend reversals. Turchin explains why: “This decline is because increasing numbers of radicals become disenchanted, as a result of high levels of political violence, leading to the rise of moderates. By the end of the cycle… the moderates reach their peak. Their collective influence results in the suppression of radicals, radicalism, and instability, signaling the start of a peaceful phase (and the beginning of the next cycle).”

Just as these secular cycles can affect the social attitudes of the populace at large, so too can they affect the mindset of the elite. In America, the elite is primarily comprised of an economic aristocracy of politicians, business owners, and educated professionals, and, Turchin writes, “the years around 1920 induced a feeling of unprecedented insecurity among the American elites. The United States was essentially in a revolutionary situation.” Decades of violence related to struggles between labor and the business owners had escalated into events described as full-blown warfare within the U.S.’s borders. The late 1800’s and early 1900’s were marked by recurring waves of strike and riots (in which people were often killed). The coal miners of West Virginia repeatedly engaged local police and military in firefights. In Colorado, railroad pinkertons sometimes massacred whole camps of workers, including women and children. There was an uptick in political assassinations.

The exhaustion from the long decades of violence, and fears over continued economic and social disruption, caused the elite to remedy the situation. “Gradually, a realization grew among many American leaders that in order to reduce instability, steps had to be taken to decrease ‘unwanted competition’ in both the economic and political arenas, and to ensure a more equitable division of the fruits of economic growth… Early steps to deal with cut-throat economic competition took the form of the Great Merger Movement, but were not as effective as business leaders hoped. Immigration laws of 1921 and 1924, on the other hand, succeeded in effectively shutting down immigration into America. Much of the motivation behind these laws was to exclude ‘dangerous aliens’… But a broader effect was to reduce labor oversupply.”

Meanwhile, business leaders such as Henry Ford had raised wages. The lack of concern for the working class that colored the Gilded Age reversed itself, in part, because the elites became more moderate when it came to their extreme capitalist ideology. Out of fears of the possibility of revolution in America, made real by the Soviet Union, the elites acquiesced to a more balanced relationship between the owners and workers. Turchin points out that while FDR and the New Deal programs didn’t get passed into law until the 1930’s, most of these proposals for jobs programs, welfare spending, and regulation already had precedent and were gaining traction in the decades beforehand. It was the shock of the economic downturn that caused the business elite to fully repudiate the old ideas and opt for social harmony. America then entered an age of prosperity.

But by the 1970’s, hardly any of the figures who were running the worlds of finance, business, or politics had directly experienced the violence of the 1910’s or 1920’s. They were not inoculated against the radical individualist ideology of extreme capitalism. The elites, meanwhile, were as a class at their economically weakest. Turchin: “During the Bear Market of 1973-82 capital returns took a particularly strong beating and the high inflation of that decade ate into inherited wealth.” The overall share of the pie held by the top of society at that time was relatively small. Thus, while one may curse the elites and wonder why they couldn’t refrain from being so greedy, we can see here the effects of social trends as in everywhere else. The elites of the 1930’s had to learn a sense of social responsibility through upheaval and hardship. Without the same lesson, the new elites coming up in the 1970’s did not have a conception of the social dissolution their rapacious behavior would bring about.

After all, the shift manifested, as it always did, in an ideological language: the language of economic dynamism, of rugged individualism, of the self-made person, of the meritocracy, and of a system based on rational self-interest. This was the language of the Reagan campaign, and accordingly the period of the “Reagan Revolution” represents the first decade completely dominated by the new trends, flowing in the direction of popular immiseration and elite acquisition. The economic troubles of the 1970’s were used as a justification for why the old economic consensus had to die; lasseiz faire capitalism became the ideal (if never quite reached in the purest sense), and the captain of industry became a heroic figure.

Turchin writes: “Although the election of President Ronald Reagan in 1980 and the beginning of ‘Reaganomics’ was its most visible symbolic manifestation, the actual cultural shift had taken place several years earlier. While the presidency of the Republican Richard Nixon continued the Great Society policies of Lyndon Johnson’s era, policy under the Democrat Jimmy Carter bore more resemblance to that of the subsequent Reagan era.”

Turchin quotes extensively from a letter of resignation from the president of the United Auto Workers, Douglas Fraser. He quotes the letter at length “because it is an excellent summary of the structural-demographic variables that are relevant to the cultural shift, which took places during the 1970s. What is particularly remarkable about the letter is that it was written in 1978 – the year when real wages stopped growing.” I include the entirety of Turchin’s quotation here, because it is perhaps the most relevant thing to understanding the zeitgeist of the 1970’s, in economic terms. Douglas Fraser writes, in 1978:

“I believe leaders of the business community, with few exceptions, have chosen to wage a one-sided class war today in this country – a war against working people, the unemployed, the poor, the minorities, the very young and the very old, and even many in the middle class of our society. The leaders of industry, commerce and finance in the United States have broken and discard the fragile, unwritten compact previously existing during a past period of growth and progress.

“For a considerable time, the leaders of business and labor have sat the Labor-Management Group’s table – recognizing differences, but seeking consensus where it existed. That worked because the business community in the US succeeded in advocating a general loyalty to an allegedly benign capitalism that emphasized private property, independence and self-regulation along with an allegiance to free, democratic politics…

“The acceptance of the labor movement, such as it has been, came because business feared the alternatives… But today, I am convinced there has been a shift on the part of the business community toward confrontation, rather than cooperation. Now, business groups are tightening their control over American society. As that grip tightens, it is the ‘have-nots’ who are squeezed.

“The latest breakdown in our relationship is also perhaps the most serious. The fight waged by the business community against that Labor Law Reform bill stands as the most vicious, unfair attack upon the labor movement in more than 30 years… Labor law reform itself would not have organized a single worker. Rather, it would have begun to limit the ability of certain rogue employers to keep workers from choosing democratically to be represented by unions through employer delay and outright violation of existing labor law…

“The new flexing of busines muscle can be seen in many other areas. The rise of multinational corporations that know neither patriotism nor morality but only self-interest, has made accountability almost non-existent. At virtually every level, I discern a demand by business for docile government and unrestrained corporate individualism. Where industry once yearned for subservient unions, it now wants no unions at all…

“Business blames inflation on workers, the poor, the consumer and uses it as a club against them. Price hikes and profit increases are ignored while corporate representatives tell us we can’t afford to stop killing and maiming workers in unsafe factories. They tell us we must postpone moderate increases in the minimum wage for those whose labor earns so little they can barely survive.

“Our

tax laws are a scandal, yet corporate America wants even wider inequities… The

wealthy seek not to close loopholes, but to widen them by advocating the

capital gains tax rollback that will bring them a huge bonanza.”

IV. Ibn Khaldun: Asabiya

In much of the discourse these days, people are prone to take stubborn stances such as the conservative cliché that “Politics is downstream of culture”. However, as we have seen, while we may well attribute the political calculations documented by Frank to be caused by the cultural shift explained by Curtis, we could just as easily claim that this cultural shift was the result of the structural-demographic forces demonstrated by Turchin. In turn, political decisions have a powerful effect on the structural-demographic trends, such that all of these components work together in various feedback loops to produce a cyclical effect. Therefore, we cannot say that it was purely a political calculation that killed the left, nor that it was simply a change in the culture. Instead, we should understand that the sociological realities governing complex societies pushed us into a disintegrative trend.

In a disintegrating society, the bonds between individuals dissolve, and communities collapse. Crime rates go up (though they will cycle, like many of these factors, from generation to generation). Economic predation from the top begins to accelerate, wealth inequality increases, and the people become distrustful of the government, of the business world, and anyone in authority. This means that people cannot rely on the institutions and associations they once trusted. Individualism becomes more rational the more people start behaving in an individualistic manner all around you.

One way of describing what happens to social cohesion during disintegrative phases is through the concept of asabiya. Turchin revivified this concept in his work, War and Peace and War, though it finds its origin in the work of Ibn Khaldun, a 14th century aristocrat and scholar from North Africa. He described the theory of asabiya in his book, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. Asabiya is the overall capacity of a group, community, or a whole society, to cooperate. Ibn Khaldun argued that asabiya was what gave an empire power: whether your people are conquered, or they themselves do the conquering, will be determined by their asabiya – their ability to stick together, act in coordination, and make sacrifices for the group’s success.

The interesting thing about Ibn Khaldun’s description of asabiya is that it prefigures what much of the work in the analysis of historical data has now shown. Of utmost importance is where is comes from, and what causes it to either increase or decline. One of the main factors was whether or not the group had to engage in conflict on a regular basis, in a struggle for its existence. A high degree of asabiya allows a group to compete as a unit against external threats, rather than competing internally against one another. When external threats continually raise their head, a group will need high asabiya to survive – and therefore, the groups that do survive will always see an increase in their ability to cooperate. We saw this effect in America, in the veterans of WWII, when Americans felt they had to band together as a society. The Greatest Generation, when they entered the ranks of government and business, tended to be very cooperative and conciliatory with their fellow Americans.

Khaldun also blamed luxury for the decline of asabiya. Turchin rejects the corrosive effect of luxury as such, but does not that ostentatious displays of wealth, which characterize cycles of elite overproduction, erode asabiya. This is because the display of wealth as status symbols and class signifiers drives intra-elite competition, which fractures the society, since the leaders of society are now competing within it rather than cooperatively directing their efforts outward. As elite ostentatious displays of wealth continue, the monetary requirements go inexorably upward, as the elite class expands and the upper crust of the elite has to find more and more expensive ways of distinguishing themselves as the true elite. This serves to close off the patriciate even further, which creates more disgruntled failed elites.

In spite of the conservative wisdom that inequality in and of itself does not harm to society, in fact, we can note that wealth inequality adversely affects the asabiya of a society, and therefore correlates with the rise of disintegrative cycles. Turchin writes: “Great differences in wealth among group members undermine cooperation, and such groups succumb to rivals with higher levels of asabiya… The growing disparity between rich and poor puts the social consensus under strain. At the same time, the gap in the distribution of wealth grows not only between the aristocrats and commoners, but also within each social group. Intra-elite competition for diminishing resources results in faction and undermines national solidarity.” The key to the understanding this is that competition against an external threat strengthens cooperation within. Competition within a society – against internal threats – fractures the overall national or societal structure. This promotes cooperation as well, but within factions, not between them. Thus, human beings are both cooperative and competitive creatures, but internal competition turns our tribalistic inclinations in the wrong direction and destroys our own society and well-being.

The disgruntled members of the elite who have been shut out of the patriciate are prone to disseminating radical ideology, which then fuels the further breakdown of asabiya. One example of a disgruntled aspirant-elite in American society is Steve Bannon, who is shown in Curtis’ documentaries speaking in the same language one might expect to hear from a devotee of Occupy Wall Street. “It was the elites, and people like you and me: people who bought into the system. And who has been held accountable? Name me one bank, one CEO, one law firm, one accounting firm. We basically just flooded the zone with liquidity. We bailed out the party of Davos. Let me say it differently. The party of Davos: the scientific-engineering-managerial-financial-cultural elite bailed themselves out. Remember: this populist movement, and Donald Trump, is not the cause of this. They’re the product of this.”

Steve Bannon is what is called a “counter-elite” – an aspirant elite who became shut out of the halls of power, and now agitates the people to radicalism. In an interview with the Atlantic, Turchin explains how Bannon fits right into the mold of a counter elite:

“Donald Trump, for example, may appear elite (rich father, Wharton degree, gilded commodes), but Trumpism is a counter-elite movement. His government is packed with credentialed nobodies who were shut out of previous administrations, sometimes for good reasons and sometimes because the Groton-Yale establishment simply didn’t have any vacancies. Trump’s former adviser and chief strategist Steve Bannon, Turchin said, is a ‘paradigmatic example’ of a counter-elite. He grew up working-class, went to Harvard Business School, and got rich as an investment banker and by owning a small stake in the syndication rights to Seinfeld. None of that translated to political power until he allied himself with the common people. ‘He was a counter-elite who used Trump to break through, to put the white working males back in charge.’ Turchin said.”

This inter-elite conflict, as noted above, fuels the breakdown of asabiya. Thus, a society which has faced no serious external threats, and with accelerating fortunes flowing to the upper ranks of society, will inevitably begin to descend into factionalism. The cultural consensus will break down entirely if things get bad enough. Figures like Bannon and Trump will continue to agitate the populace into rebellion: but this is because of the underlying sociological forces, and not because they are either stalwart crusaders for the working man nor because they are evil racists. Even if one removed the current counter-elite from the equation, the sociological forces will continue to produce new counter-elites.

Another central pillar of Khaldun’s idea of asabiya is religion. The ready example is Islam, which had, a few centuries before he was born, completely reshaped the political reality of the world in which Khaldun lived. Turchin documents how the Muslim religion acted as a force to unite disparate tribes and ethnicities into organized states. Khaldun says that religion “does away with mutual jealousy and envy among people who share in an asabiya... nothing can withstand them, because their outlook is one and their object is of the common accord. They are willing to die for their objective.”

All of these factors play a role in determining a society’s

capacity for cooperation: whether there is a shared set of beliefs or

values (religion), how extreme the inequality in the distribution of

wealth, and whether there is the uniting influence of external threats.

These factors seemed to wax and wane. Turchin

describes, in this book, how Ibn Khaldun began to perceive the cycles

that govern human history. Khaldun noted how the desert tribes lived a

hard existence that fostered high asabiya. Meanwhile, the settled

civilizations seemed to lose their asabiya after the harsh reality of

desert survival and tribal warfare disappeared and was replaced by comfort. Turchin summarizes:

“Ibn Khaldun noticed that political dynamics in the Maghreb tend to move in cycles. When a state in the civilization zone fells into internal strife, it becomes vulnerable to conquest from the desert. Sooner or later, a coalition of Bedouin tribes is organized around one group with a particularly high asabiya. When this coalition conquers the civilization zone, it founds a new state there…

“As generations succeed generations, however, the conditions of civilized life begin to erode the high asabiya of the former Bedouins. Generally speaking, by the fourth generation the descendants of the founders become indistinguishable from their city-dweller subjects. At this point, the dynasty goes into a permanent decline…”

Turchin confirms in War and Peace and War that asabiya follows a cyclical pattern, tied to the secular cycles. “Decline of asabiya is not linearly uniform. During the integrative phases of secular cycles when inequality is moderate, intra-elite competition and conflict between elites and commoners subside; the empire-wide identity regains its strength, for a time… it takes the cumulative effect of several disintegrative phases to reduce asabiya of a great imperial nation to the point where it cannot hold together its empire.”Needless to say, we’re now in a period of disintegration that began with the 1970’s, which means we should expect to see American asabiya continue to decline for at least another 30-40 years. Politically, this means that while we may have some signs of progressivism rising, here and there, the overall trend will be towards a meritocratic attitude which justifies the current status quo and the dominance of the managerial elite. Workers will be helped only to the degree that they can still go on working and not starve en masse. The Washington consensus on policy will continue to drift further and further from the popular will. Radical ideas, meanwhile, will continue to spread like wildfire, but the sclerotic rule of the current elite will continue for as long as possible, as no one individual will want to give up their wealth and power – and will justify this decision within an individualist mindset, or at least a zero sum-“if not me, it would be someone else”-mindset.

V. A Rough Sketch of the Continuing Trends

It is worth a brief run-through of our history from the 1970’s until to the present moment, through the perspective of politics, culture, and cliodynamics. The facts bear out the notion that the 1970’s were the beginning of a trend, and not an isolated blip in the data.

As has been briefly mentioned, the 1980’s were the era of the Reagan Revolution. This coincided with the rise of Thatcher in Britain, and was the intersection of both the politics and culture of individualism. Reagan preached a blunt, uncompromising American exceptionalism, describing America as the leader of a powerful, divinely-ordained free world, battling against collectivist tyranny. As is commonly known, the economics of Reagan emphasized the need to free businesses from regulation and cut taxes for the upper crust of society to fuel dynamism. Reagan meanwhile criticized the bottom rung of society: the “welfare queens” who parasitized the system.

This sea change was not limited to the Executive branch. As we have already mentioned, there was a new crop of Democrats in Congress, exemplified by Gary Hart, who identified as neoliberals, spoke in rhetoric of individualism, and legislated a pro-business economic agenda. Similarly, on the Republican side of the aisle, the Young Republicans emerged. They were defined by their critical stance towards the party leadership, and their opposition to compromise. They included Newt Gringrich (elected 1978), Vin Weber (1980), Dick Armey and Tom DeLay (1984).

During the Reagan presidency, the anti-union action from the government accelerated. Turchin calls the definitive turning point the defeat of the airline worker’s strike in 1981. Meanwhile, the top-marginal tax rates continued to be slashed. Earlier reductions in tax rates had occurred in the 1960’s and 1970’s, but these only served to bring the top rate down to WWII-era levels, which was around seventy percent. The tax cuts in the 1980’s saw these rates fall to around thirty percent.

In terms of the cultural shift, Adam Curtis’ films use the examples of the formerly counter-cultural or revolutionary figures to show how the 1980’s accelerated the individualist ideology. Jane Fonda, a political radical who had even gone so far as to visit the communist North Vietnamese fighters during the U.S. war in Vietnam, wrote a best-selling exercise book in the 1980’s. It was adapted to a film in 1982, which became the most successful home video up to that point, selling over a million copies – and making Jane Fonda a very successful capitalist. “Jane Fonda gave up on socialism and started another revolution,” the text reads, emblazoned across the screen as footage rolls from Jane Fonda’s tape. Curtis directs us to consider, through the footage and images, how the hyper-individualistic society began to lose its social bonds and any cultural notion of the sacred, which leads inevitably to self-preservation as the highest value. This means that health and fitness become of utmost importance – which is big business.

Meanwhile, one of the Black Panthers – Bobby Seale, the man whose powerful speech in Harlem converted Tupac Shakur’s mother, Afeni, to the cause of revolutionary racial justice – released a cookbook in the late 1980’s. Curtis shows footage of Seale on a TV cooking show, introduced as both a barbecue chef extraordinaire, and one of the founding members of the Black Panther party. Another black radical became a high concept fashion designer, who created a brand of “revolutionary” pants that would “free the penis”.

The 1980’s also saw the crack epidemic sweep the black communities in the United States, which carried with it waves of gang-related violence. Tupac Shakur, who became a famous rapper, at first attempted to use his music in the early 1990’s to raise awareness about how the entire community was affected by the social forces that destroyed its individual members – that is, how addiction, inner city violence, and single parenthood was corrosive to any sort of brotherhood that could allow the black community to solve their problems. But, in an escalating attempt to prove his authenticity in the “thug life”, Shakur pushed further into criminality and violence. He was famously killed in a drive-by shooting. Curtis quotes one of the radicals at the time, who wrote, “Thug ambition is completely predatory, because it totally ignores the fellow-feeling required for collective action.”

In the meanwhile, the Democrats in Congress had pushed through the 1994 Crime Bill, which exploded the incarceration rate. The radicalism expressed through art and music during the period seemed entirely disconnected from the political aims of the supposedly “left” political party. This was because individual expression cannot challenge power. The fears of the white suburbanites, who were increasingly paranoid about inner-city crime – in spite of the falling crime rate at the time – were a more powerful motivator for Washington than what radical artists had to say. And thus, the party that still claimed to represent the blacks and the underclass locked millions of them away with no chance of parole, sometimes for minor offenses – often drug offenses.

The 1994 Crime Bill, of whom now-President Joe Biden was the architect, was signed by then-President Bill Clinton. Clinton was the first Democratic president since the time of the Reagan Revolution. While Carter had already begun the political capitulation to the economic elites, his term ended a full twelve years before Clinton took power. Clinton was therefore the first Democratic president to reign from a fully neoliberal ideological bent. He had been shaped and molded by an institution that formed within the Democratic party to produce just such a politician.

That institution, that emerged to represent the power of neoliberal thought in the Democratic party, was the Democratic Leadership Council, or DLC. The DLC pushed the Democratic party to represent the overlooked middle American, and to move to the center politically. In effect, they were squabbling with the Republican party over their relative shares of white-collar voters, while continuing to ignore the lower classes. By the early 1990’s, the DLC’s rhetoric was consistently that the Democrats had to move beyond left and right. During this time, the language of “triangulation,” or “the third way”, or a “new way”, began to become very popular. Bill Clinton was the embodiment of this new way.

Thomas Frank detailed the economic devastation wrought during the Democratic control of the government during those years. Clinton oversaw a massive deregulation of Wall Street. When interstate banking was deregulated in 1994, one prominent banker said that it would “let the strong take over the weak so that we can move forward.” There was also a push for electricity deregulation, and a telecommunications deregulation in 1996. The capital gains tax cuts of the Clinton era were “one of the most regressive tax cuts in America’s history”, according to Joseph Stiglitz, who chaired Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisors. The repeal of Glass-Steagall was perhaps the most extreme example of the nakedly obvious alignment of the Democrats with the professional-managerial class. Glass-Steagall had separated commercial from investment banking since 1933, but was now often ridiculed as a “Depression-era barrier” to progress. A New York Times story in 1995 reported that, among lawmakers, “Almost everybody agreed that Glass-Steagall was an anachronism in a global economy… the act is widely viewed today as a drag on the economy.” Its repeal was one of many such moves that set the stage for the financial crash of 2008, as Stiglitz himself later argued. By merging the investment and commercial banks, the investment-banks inevitably came out on top, and dominated the culture of the banking world. Whereas Glass-Steagall had reigned in risky investments, now they became the norm.

|

| Bill Clinton, surrounded by congressional lawmakers, the moment he repealed Glass-Steagall |

Meanwhile, the disdain for blue-collar workers intensified. In a speech in December 1992, the newly-elected Clinton expounded upon this ideology in simple, direct terms. “Our new direction must rest on an understanding of the new realities of global competition. The world we face today is the world where what you earn depends on what you can learn.” In the DLC’s magazine in 1995, the uneducated working class were compared to “illiterate peasants in the Age of Steam.” Later, a 1998 manifesto distributed by the DLC put it even more bluntly: “The new economy favors a rising learning class over a declining working class.”

After Bill Clinton carried the neoliberal ideology into the White House, he effected a complete transformation of the Democratic party. The presidencies of Barack Obama and Joe Biden, as well as the candidacy of Hillary Clinton, have simply been variations on this same theme. Neoliberalism, however, as it should be now be clear, is a thoroughly anti-labor, pro-PCM (professional-managerial class) ideology. Neoliberalism thrives on culture war, ignores economic populism, and has a utopian view of technology and the future, and in the idea that society will be fixed by entrepreneurial saviors, and educated social scientists. Tech-utopian ideas have also been discussed in Curtis’ documentaries at length, and are perhaps beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice to say, the idea of a smart, innovative businessman who will step in to save society fits right into the idea of hyper-individualism.

The inevitable result of the Democratic governance in the style of Clinton-Obama-Biden was the total alienation of the laboring classes from the Democratic party. As we have already hinted at, the consequences of this abandonment began to be felt most strongly because of the election of Donald Trump, who promised to salvage a forgotten America. He promised to bring the old manufacturing jobs back, to impose protectionist trade policy, and limit immigration. He largely failed on all of these accounts, but won himself a loyal personality cult because of the power of his rhetoric. Meanwhile, Clinton’s dismissals of the disintegration of middle America likely cost her the election – Trump won less votes in 2016 than Republican challenger Mitt Romney did in 2012 when he was defeated by incumbent Barack Obama, meaning that Clinton simply could not galvanize support for her campaign to the level that past Democrats had.

The economic downturn caused by the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020, led to such a degree of public frustration that Trump was unseated by Biden, with record voter turnout for both parties. However, some have compared this election to many elections of the Gilded Age, where there was similarly high voter turnout, but little in the way of substantive policy differences between the two parties. Primarily, the divide between the two parties has become cultural. Given that we are in what Turchin calls a Second Gilded Age, perhaps this should be unsurprising. The most important point is that the underlying trends which produced the Trump phenomenon have not abated, and until they do, we should not expect the polarization to change, or government to become more responsive to the economic needs of the people. Elite overproduction has meanwhile increased to a massive level, with more millionaires per the general population than ever in U.S. history, and skyrocketing costs for entry into the upper echelons of society. This means more internal conflict is coming.